The Progenitor of All Pop Culture Zombies

This writer introduced zombies to America. He also ATE HUMAN FLESH.

The latest season of the Paris-based spin-off of The Walking Dead is airing on AMC right now. Meanwhile opportunistic politicos are pushing viciously racist falsehoods about Haitian people and what they eat. The confluence of these two things has me thinking about William Seabrook.

Seabrook introduced the term “zombie” to America after he learned of the mythical creatures during a visit to Haiti. He was also a self-confessed cannibal who wrote in excruciating detail about the smell, texture, and taste of freshly cooked human flesh.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Seabrook was a bohemian, an occultist, a sadomasochist, and a journalist who mixed high-minded literary aspirations with a knack for base sensationalism. In 1929, he released the travelogue The Magic Island, in which he described Haitian culture and religious rituals.

Seabrook prided himself on transcending the bigotry, conventionality, and superstitions of his upbringing in the Reconstruction-era South. He wanted to write about voodoo as dispassionately as he might write about Protestantism. But his book-length investigation of “black sorcery” looks incredibly racist and condescending in a modern light. (His writing was accompanied by a series of illustrations by Alexander King that now seem equally offensive.)

Here is how Seabrook says that the supernatural phenomenon of human reanimation was explained to him during his time in Haiti:

While the zombie came from the grave, it was neither a ghost, nor yet a person who had been raised like Lazarus from the dead. The zombie, they say, is a soulless human corpse, still dead, but taken from the grave and endowed by sorcery with a mechanical semblance of life—it is a dead body which is made to walk and act and move as if it were alive. People who have the power to do this go to a fresh grave, dig up the body before it has had time to rot, galvanize it into movement, and then make of it a servant or slave, occasionally for the commission of some crime, more often simply as a drudge around the habitation or the farm, setting it dull heavy tasks, and beating it like a dumb beast if it slackens.

The idea of zombies as cannibals with an insatiable hunger for human flesh is a more recent invention, with no connection to Haitian lore.

In The Magic Island, Seabrook explains what the actual dietary needs of the original zombies were reputed to be. He shares the story of a Haitian couple, Joseph and Croyance, who command a group of field workers that are “not living men and women but unhappy zombies who [they] had dragged from their peaceful graves to slave in the sun.” Croyance must prepare tasteless meals for them because zombies die if they taste salt or meat. One day she takes pity on the “poor dead creatures who should be at rest,” and decides that it might cheer them to see the crowds and processions in the city during a religious festival.

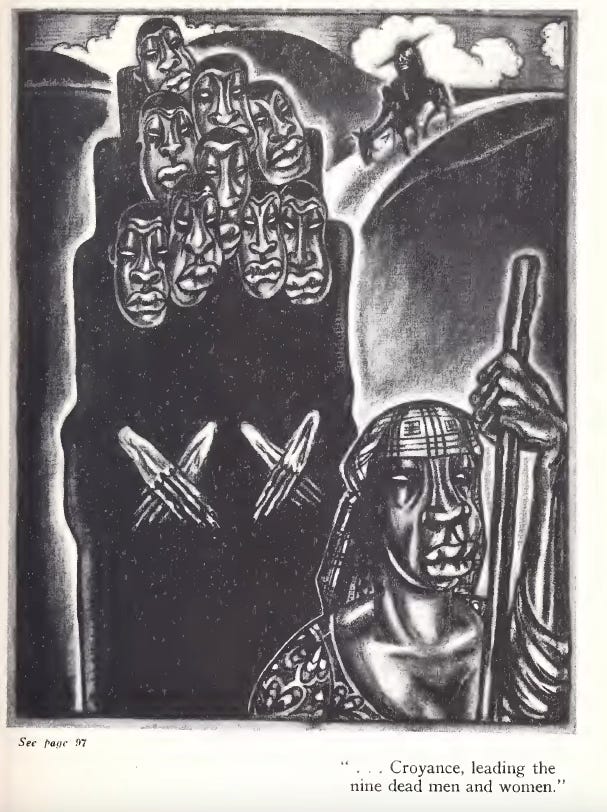

So she tied a new bright-colored handkerchief around her head, aroused the zombies from the sleep that was scarcely different from waking, gave them their morning bowl of cold, unsalted plantains boiled in water, which they ate dumbly uncomplaining, and set out with them for the town. Croyance, in her bright kerchief, leading the nine dead men and women behind her, past the railroad crossing, where she murmured a prayer to Legba, past the great white-painted wooden Christ, who hung life-sized in the glaring sun, where she stopped to kneel and cross herself—bu the poor zombies prayed neither to Papa Legba nor to Brother Jesus, for they were dead bodies walking, without souls or minds.

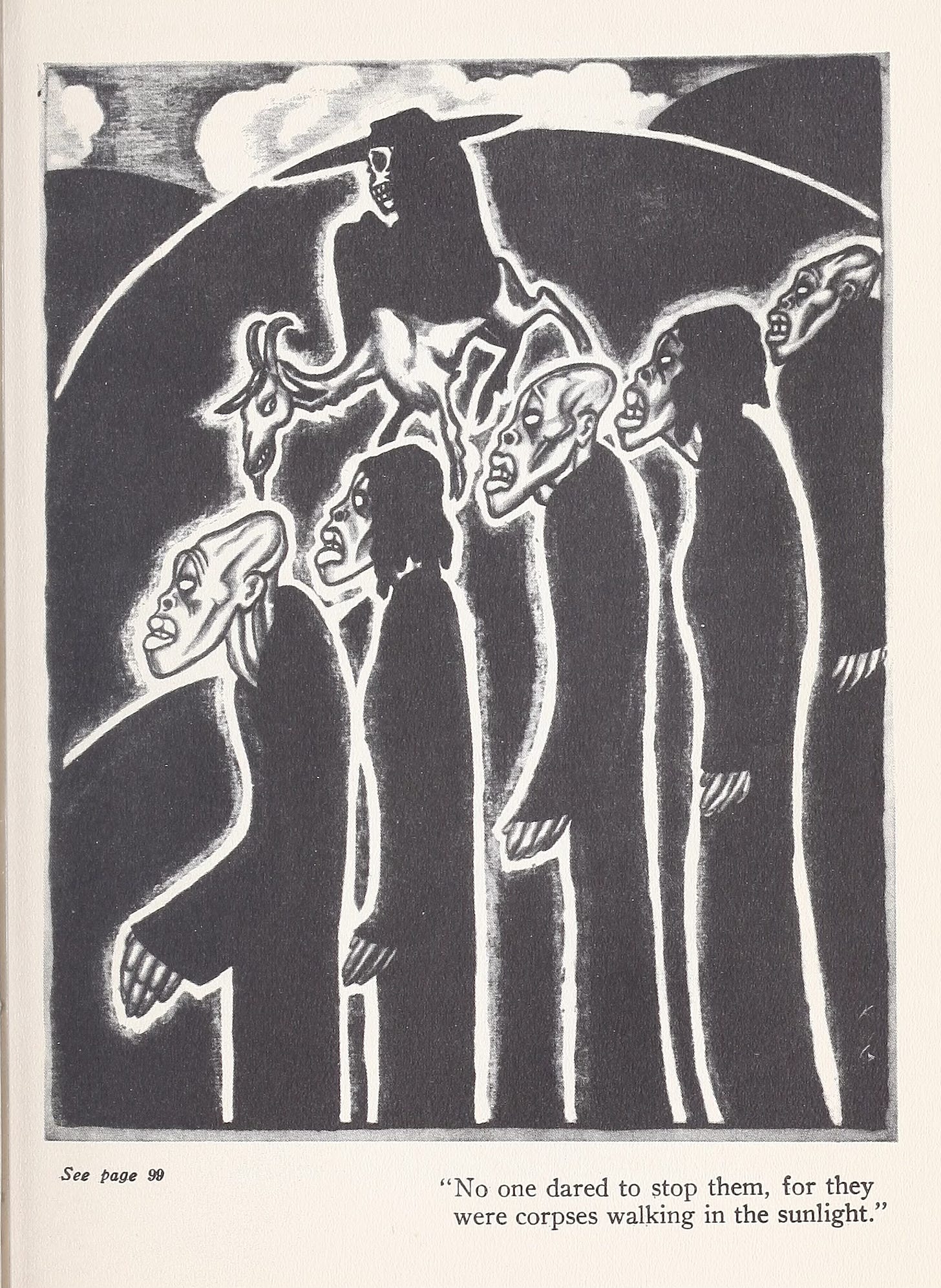

In town, Croyance slipped up and mistakenly fed salted pistachios to the zombies. The tasty seasoned food broke the spell that had suspended them in an unnatural state between life and death; they all cried out, and then they each began to trudge towards the graveyards in their home villages. “No one dared stop them, for they were corpses walking in the sunlight, and they themselves and all the people know that they were corpses.”

When they reached their destinations, each of the zombies fell to the ground and immediately transformed into a pile of rotting flesh.

Seabrook records that he had several supposed zombies pointed out to him, but he eventually concluded, “Zombies were nothing but poor, ordinary demented human beings, idiots, forced to toil in the fields.” When the book was published, he felt that he had delivered a serious ethnographic study. But he was canny enough and cynical enough to play up the most exotic aspects of Haiti at every turn. And doing so helped to gauarantee massive sales.

The mythos of voodoo and the idea of corpses reanimated by means of dark magic immediately struck a chord in American popular culture. Within a few years of the publication of The Magic Island, zombies had become a staple of the horror genre.

Many were eager to exploit the sudden fascination with the walking dead. A Broadway production called Zombie opened in early 1932. This “play of the tropics” was supposedly so bad that it closed almost immediately. It was restaged out of town as a comedy rather than a pulse-pounding thriller.

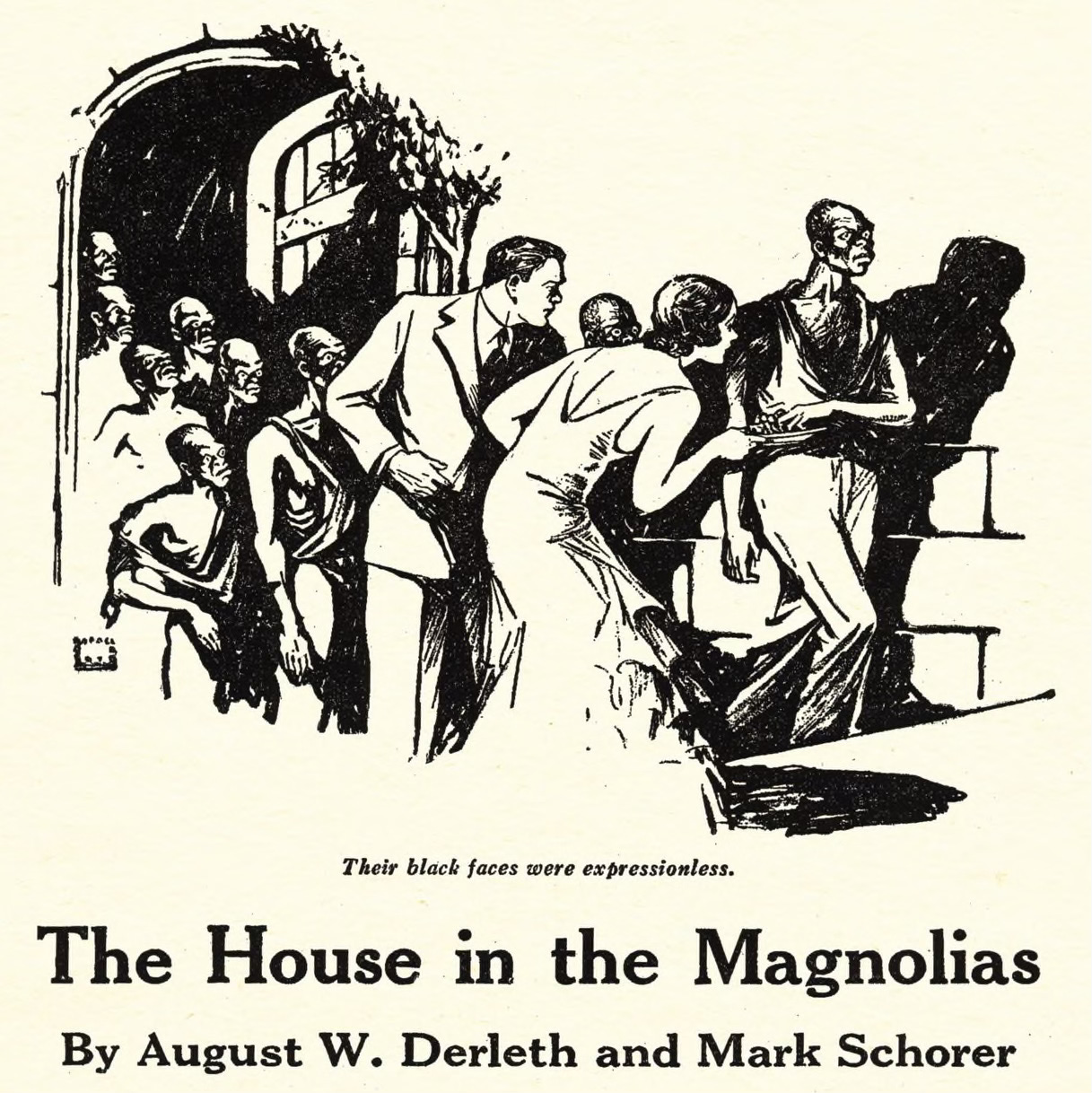

In June 1932, the pulp magazine Strange Tales Of Mystery And Terror published a short story “The House of the Magnolias.” It transplanted the zombie mythos to a plantation outside of New Orleans, with black zombies toiling through the night in the fields. A visitor took pity on them and fed them salted candy, releasing them from their cursed existence. But before these zombies returned to their graves, they took revenge on their slave master, burning the plantation house to the ground.

The original zombie mythos and the earliest zombie stories in American pop culture focused on the metaphor of slavery and forced labor. In July of 1932, White Zombie, the first zombie horror flick, was released. Boris Karloff portrayed a voodoo priest named Murder Legendre who created an undead workforce to toil in his sugar mill.

Seabrook himself was obsessed with captivity and subjugation throughout his life. He used a portion of the wealth that his zombie book brought him to hire women who would allow him to strip them naked, chain them up for days at a time, and force them to eat table scraps from the ground like an animal. He believed that the deprivation allowed them to enter a heightened psychic and spiritual state—it was all just part of his questing exploration of the outer limits of mysticism, you see. (He even wrote a book about it.)

The idea of zombies as violent creatures driven by an insatiable desire for human flesh wasn’t established until the 1968 release of Night of the Living Dead. The director George Romero never intended for his reanimated corpses to be seen as zombies, and the z-word is never used in the film. But the impact of this grisly low-budget masterpiece on the horror genre was so immense that cannibalism quickly fused with the Haitian mythos. Dead people attacking and devouring living people became the core trope of zombie lore.

But William Seabrook got to cannibalism first, decades before the Romero film.

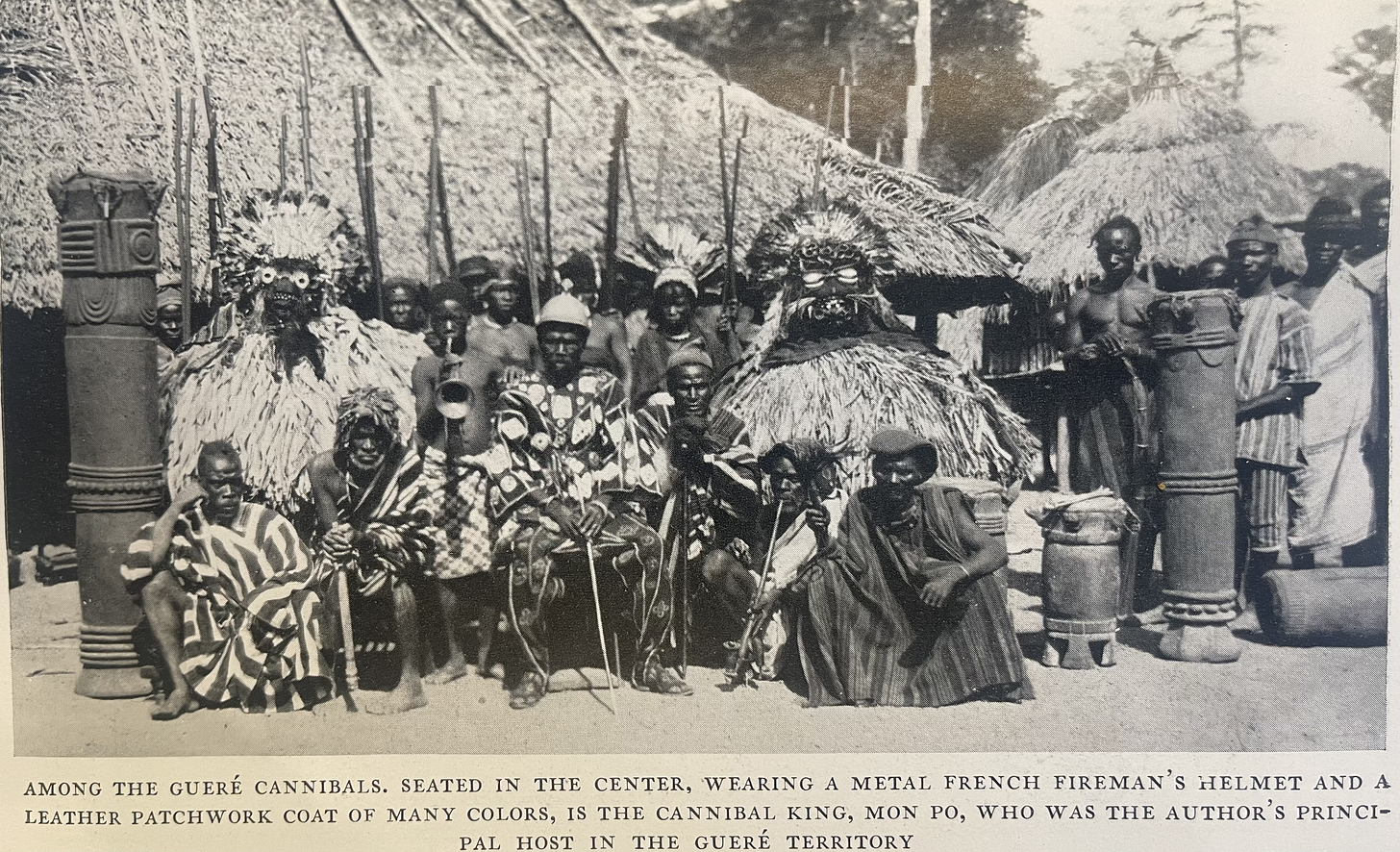

In 1930, he released the book Jungle Ways, in which he wrote openly, unashamedly—boastfully even—about eating human flesh The writer’s fascination with the “exotic” rituals of BIPOC people (and the confidence that the book-buying public would reward him handsomely for doing so) compelled him to seek out an African tribe that was reputed to have engaged in ritualistic cannibalism. He wanted to explore the outer edges of human behavior, shatter taboos, and épater la bourgeoisie. And oh brother, did he ever.

While researching the Guere tribe in French West Africa, he concluded that cannibalism was unthinkable in Western cultures that “believe that in the essence of a man there is something holy which other animals have not.” But the Guere, like many cultures around the world, believe that everything has a soul and that it’s therefore unavoidable to eat things that contain the divine spark. Seabrook records his personal eureka moment about cannibalism:

I was compelled to say finally, “I can’t seem to think of any reason why you others shouldn’t eat it if you like it.” And I added, “As a matter of fact, I should like very much to try it myself, just once.”

“If you like it.” He reduces the practice to a mere food preference, as if these people were choosing between trout and pork chop on a restaurant menu.

For the Guere, cannibalism wasn’t a matter of sustenance. It had been part of an elaborate series of rituals that only took place in the context of a vanquished opponent in war. The Guere refused to let Seabrook, who had no connection to their culture or their beliefs, take part in their practice. In fact, they insisted that the practice had been discontinued long before his arrival.

At one point, the Guere gave in to the writer’s unceasing pestering and went through the motions of serving him a cannibal feast. The writer later deduced that they used subterfuge, feeding him ape meat.

But Seabrook didn’t let this deter him.

In Jungle Ways, the writer claims that he later managed to obtain some cuts of human flesh—small chunks of meat suitable for stew, “a sizeable rump steak, also a small loin roast.” He assured his readers that it was the result of an accidental death, “the meat of a freshly killed man, who seemed to be about thirty years old—and who had not been murdered.”

Seabrook was cagy about how he acquired this corpse flesh, and he insisted that it would be “unfair, unsporting, and ungrateful” to reveal the identity of whoever hooked him up. He would later reveal in his 1942 autobiography that an acquaintance obtained it for him from an internist at the Sorbonne who had access to the facility’s morgue.

In Jungle Ways, the writer explained how he prepared these cuts of human meat for consumption, spitting the loin roast, grilling the rump steak, and mixing the stew with rice. He described the sensory experience of the process at length:

The raw meat, in appearance, was firm, slightly coarse-textured rather than smooth. In raw texture, both to the eye and to the touch, it resembled good beef. In color, however, it was slightly less red than beef…the aroma was wholly pleasant, like those of beefsteak and roast beef, with no special other distinguishing odor…the fat was sizzling, becoming tender and yellower. Beyond what I have told, there was nothing special or unusual. It was nearly done and looked and smelled good to eat.

Seabrook was determined to dine upon these pieces of a former person. And not just dainty little nibbles! “It would have been stupid to go to all this trouble and then taste too meticulously and with too much experimental nervousness only tiny morsels…I had thought about this and planned it for a long time, and now I was going to do it.”

The writer records that he took his first bite and was pleased and relieved to discover that he had no physical revulsion or moral compunctions about what he was doing. “It had no weird, startling, or unholy special flavor.” He went on to describe the taste and texture of human flesh in exacting, appalling detail.

“It was like good fully developed veal, not young, but not yet beef... It was mild, good meat with no other sharply defined or highly characteristic taste such as for instance, goat, high game, and pork have. The steak was slightly tougher than prime veal, a little stringy... The roast, from which I cut and ate a central slice, was tender, and in color, texture, smell as well as taste, strengthened my certainty that of all the meats we habitually know, veal is the one meat to which this meat is accurately comparable…A small helping of the stew might likewise have been veal stew, but the overabundance of red pepper was such that it conveyed no fine shading to a white palate.”

Of course, of course, he brings race into it again. And it’s so telling that a little bit of cayenne overwhelmed his gringo honky senses, but the moral issues of what he was doing never gave him pause. “Neither then nor at any time since have I had any serious personal qualms, either of digestion or of conscience,” he insists.

This unrepentant cannibalism was too much even for the sensation-starved public that had embraced Seabrook’s earlier tales of voodoo and zombies. In his 1942 autobiography, the writer quotes a review of Jungle Ways in the Montgomery Advertiser that captures the tenor of the public disgust: “It is not agreeable to think that an intelligent, educated member of the white race and of the American nation, has voluntarily descended to a scale lower than that observed by these lowly peoples.”

In Seabrook’s telling, he had been castigated and condemned for his broadmindedness and universalism, not for eating human flesh. “Those who might have forgiven me for eating a n——r couldn't forgive me for eating with one,” he wrote.

Seabrook knew that he would be remembered for his flirtation with cannibalism and for touching off the zombie craze, not for his lofty literary pretensions or his desire to be a world-bridging truth-teller. That tormented him, and he in turn tormented those around him. He would die in 1944 after downing several handfuls of sleeping pills and a bottle of hooch. His former friend, the satanist Aleister Crowley, wrote, “The swine-dog W. B. Seabrook has killed himself at last, after months of agonized slavery to his final wife.”

Seabrook was smart enough and self-aware enough to grasp that all of his vaunted taboo-busting had ultimately been about his own wealth, notoriety, and self-gratification.

READ MORE ABOUT IT:

William Seabrook. The Magic Island (1929)

William Seabrook. Jungle Ways (1930)

William Seabrook. No Hiding Place: An Autobiography (1942)

Marjorie Muir Worthington. The Strange World of Willie Seabrook (1966)

Emily Matchar. The Zombie King (2015, The Atavist Magazine, No. 45)

Joe Ollmann. The Abominable Mr. Seabrook (2017, graphic novel)